It’s become a common shtick to ask why Australian politics seems to be very different from the rest of the Western world. Across the world, there is growing disenchantment with politics and existing institutions. Major parties on the centre-left and centre-right are struggling against insurgent challengers on the Left and Right, both internally and externally. It manifests in a common question that gets asked in progressive circles: Why don’t we have the equivalent of Sanders or Corbyn in Australia?

The short answer is that both are products of a particular context. Nothing happens in a vacuum. It does not happen without the broader politicisation that is occurring elsewhere.

Both Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn products of particular contexts, cultures and history. Corbyn is the product of a hard left tradition in the British Labour Party no longer exists in the ALP. In part, due to the discipline of the ALP and the emergence of a viable challenger on its left flank in the Greens. Sanders is a former Mayor in a small state, someone who has been outside the Democratic Party for all of his political career, arguing on a platform of democratic socialism as a candidate for Democratic nomination. There is no equivalent for the pathway Sanders took in Australia.

Both took advantage of unique conditions: open primaries in two-party dominant systems combined with a rejection of technocratic centre-left politics by a reshaped party base. It was fuelled by radicalisation that has happened in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, supported in particular by younger votes.

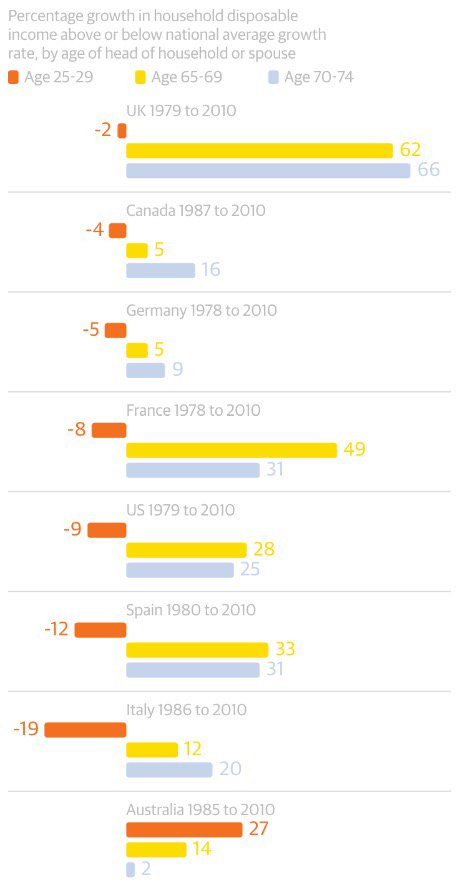

As Jason Wilson has noted, Australia has an outlier to this seemingly global trend of a strengthening Left. His argument is that the economic circumstances is the key difference. A recent Guardian feature on Generation Y seems to affirm this, a graph based on Luxembourg Income Study Database data showing that disposable income for Generation Y in Australia increased over three decades while elsewhere it was flat or decreased.

While there are issues with the data, it does provide a clear picture. Young people in the rest of the world have gone backwards, not just since the Global Financial Crisis but for over a decade. The angers and frustrations expressed have been built up over a long period of time and are directly linked to falling standards of living.

My view is that the radicalisation that has occurred elsewhere will happen but hasn’t yet. There is an underlying dissatisfaction with politics. Young people are particularly concerned about the future, whether they will have a permanent job or be able to afford housing. That undercurrent was shown by the reaction to Richard Cooke’s essay on the boomer supremacy. Income growth has slowed since 2010, the affordability housing is a problem as are difficulties with finding decent secure permanent jobs amongst young educated people. The future they were sold is not appearing. The crunch has not happened and there has not been a catalyst.

Our electoral system, buttressed by preferential and compulsory voting as well as single member electorates, helps to cover up the extent of disengagement and disenchantment. There are anti-system votes for minor parties and support for politicians that seem to buck it but not a systematic challenge. An economic crisis may be what pushes people over the edge. If we do face a full-blown economic crisis, we may see that undercurrent turn into popular anger against a system that represents the state to the people rather than representing social bases.

If does happen here, however, there is no guarantee that it will come through the Labor Party or even the Greens. The closed nature of our parties makes it difficult for that surge to go through any existing well-established party. Furthermore, both Sanders and Corbyn have also been longstanding figures, there is no equivalent in any existing party that could play a similar role.

A new political formation will not be the immediate response. The emergence of social movements and its transmission into politics takes time. It is not immediate. Podemos, Corbyn, SYRIZA, Sanders, the HDP in Turkey, the New Power Party in Taiwan, none of appeared immediately. Arguably it was a defeat on the streets and realisation that they needed to take state power that compelled them to form political parties. It is similar to the decision made by Australian unions in the 1890s after the Maritime Strike. Their success also took years, not months and only gained considerable strength after they seemed like viable vehicles.

If this politicisation does emerge in Australia, it is unclear that it will benefit the Left. The reaction against establishment politics in many parts of Europe have not benefitted the Left but a reactionary Right, particularly in Central, Northern and Eastern Europe. The anti-establishment mood has not taken a left versus right stance but rather a people versus the elites/oligarchs/cartels.

Could we see something more like Trump here? A populist who denounces the corrupt elite but supports public spending is quite possible as Australia has not been immune to those outbursts of right-wing populism – One Nation and Clive Palmer being two notable recent examples. It is hard to predict because national factors play a huge role in how anti-system energies are channelled and barriers to entry are much higher here than elsewhere. Events and the response of strong personalities will play a big role in what happens.

Whatever does occur, it won’t be the same as North America or Western Europe. There is no guarantee that the established Left or the Right will benefit from anti-system energies. We won’t have a Corbyn or Sanders because our recent experience has been considerably different but like elsewhere a people versus oligarchic elites narrative is likely to dominate.